Welcome to BisPy’s documentation!¶

BisPy is a Python library for the computation of the maximum bisimulation of directed graphs.

A brief introduction to bisimulation¶

Consider a graph \(G = (V,E)\). A bisimulation \(\mathcal{B}\) is a binary relation on \(V\) which satisfies the following condition:

The definition may be read as follows: given a pair of two nodes which are in relation with respect to \(\mathcal{B}\), each child of the first node is in relation with at least one child of the second node, and viceversa.

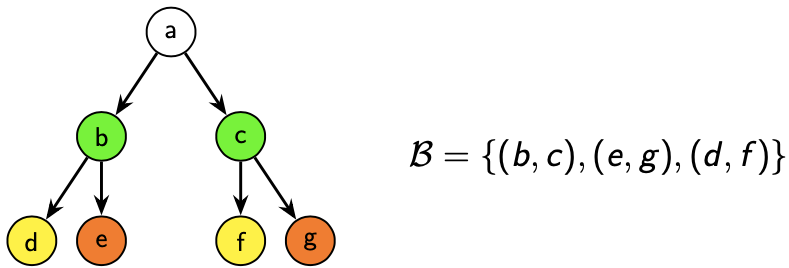

The following image shows an example of a bisimulation:

In the image above an interesting property of bisimulation emerges: two bisimilar nodes (namely two nodes in relation for at least one bisimulation on the graph) always behave in a similar way, in the sense that all their children behave in a similar way, which is exactly the condition stated above.

Another (simpler) example:

Again, the two nodes are almost indistinguishable: we may switch \(a\) and \(b\), and (apart from the name) nobody would notice the difference. This is a consequence of the fact (which can be proved) that two bisimilar nodes represent the same set.

It’s easy to see that in general there are more than one bisimulations on a graph. For instance the empty relation (\(\mathcal{B} = \emptyset\)) or any trivial reflexive relation \((\mathcal{B} = \{(a,a), (b,b), \dots\}\)) are all bisimulations. The maximum bisimulation of a graph is the bisimulation which results from the union of all the other bisimulations on that graph. It can be shown that this binary relation is still a bisimulation, and also an equivalence relation.

For the reasons which we stated above, we see that the maximum bisimulation conveys a lot of information about the nodes of the graph and how they behave. Its equivalence classes contain nodes which are equivalent two by two in the sense of bisimulation. Therefore they all behave in the same way, and we remark that this means that all their children behave in the same way.

The bisimulation depicted in the first image is not the maximum bisimulation, since even though nodes \(d,g\) are bisimilar they are not in relation with respect to \(\mathcal{B}\). In fact, the maximum bisimulation is the following relation:

Applications

Maximum bisimulation may be used to find equivalent nodes (a task which has a lot of applications in concurrency theory and indexing of semi-structured datasets, for instance) or to minimize the graph (by collapsing each equivalence class into a single node) while preserving the information conveyed by the graph.

Equivalence with RSCP

It can be shown that finding the maximum bisimulation is equivalent to finding the Relational Stable Coarsest Partition (RSCP) of the set \(V\) with respect to the relation \(E\). This problem consists in finding the coarsest (i.e. the one with fewer blocks) stable partition of the set \(V\), where stable means that for each couple of blocks \(B_1,B_2\) the following condition holds:

This equivalence is widely exploited since the RSCP problem is easier to express algorithmically.

References

The interested reader may found an in-depth discussion in the following paper:

Gentilini, Raffaella, Carla Piazza, and Alberto Policriti.

"From bisimulation to simulation: Coarsest partition problems."

Journal of Automated Reasoning 31.1 (2003): 73-103.

Contents¶

Bibliography¶

The following is a non exaustive list of references which we consulted during the development of the project:

- Saha, Diptikalyan. "An incremental bisimulation algorithm."

International Conference on Foundations of Software Technology

and Theoretical Computer Science.

Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007.

- Dovier, Agostino, Carla Piazza, and Alberto Policriti.

"A fast bisimulation algorithm." International Conference on

Computer Aided Verification.

Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2001.

- Gentilini, Raffaella, Carla Piazza, and Alberto Policriti.

"From bisimulation to simulation: Coarsest partition problems."

Journal of Automated Reasoning 31.1 (2003): 73-103.

- Paige, Robert, and Robert E. Tarjan.

"Three partition refinement algorithms."

SIAM Journal on Computing 16.6 (1987): 973-989.

- Hopcroft, John.

"An n log n algorithm for minimizing states in a finite automaton."

Theory of machines and computations. Academic Press, 1971. 189-196.

- Aczel, Peter.

"Non-well-founded sets." (1988).

- Kanellakis, Paris C., and Scott A. Smolka.

"CCS expressions, finite state processes, and three problems of equivalence."

Information and computation 86.1 (1990): 43-68.

- Sharir, Micha.

"A strong-connectivity algorithm and its applications in data flow analysis."

Computers & Mathematics with Applications 7.1 (1981): 67-72.

- Cormen, Thomas H., et al.

Introduction to algorithms. MIT press, 2009.